Over the next few sections we will explore how digital media has evolved and games become the apex of storytelling through their interactive nature. If there are concerns about the negative impacts they might have on our day-to-day life, especially during developmental years, we will also be looking at if and how violence and aggressive behaviours of the interactive realm of video games have any carryover into real-world contexts.

Avatars, players & NPCs

In the intricate realm of video games, players navigate through a dynamic landscape populated by various entities, each serving distinct roles. The protagonist, often an embodiment of the player’s agency, engages with the game world, influencing its narrative and outcomes. Avatars, on the other hand, represent the player within the game, acting as an interface between the user and the virtual environment. Non-Player Characters (NPCs) are entities controlled by the game itself, contributing to the overall storyline or providing challenges for the player. Additionally, the presence of other players introduces a social dimension, allowing for interactions, collaborations, or conflicts within the gaming environment.

Avatars

Caption: A group of customisable online avatars

The relationship between players and in-game characters, particularly avatars, plays a crucial role in shaping how individuals perceive and respond to violent acts within the gaming experience. According to Banks (2015), this player-avatar relationship spans a continuum from asocial to fully social experiences. At the asocial end, players view their avatars merely as objects for gameplay, devoid of emotional attachment. In contrast, fully social experiences involve players recognising avatars as distinct and authentic social entities.

Empirical exploration of these player-avatar relationships (PAR) is still underway, but potential implications for responses to interactive media violence emerge. Players with an asocial orientation towards their avatars may perceive violent content as a distant and amoral consequence of gameplay. Consequently, they might be less inclined to critically evaluate the violent elements, a tendency associated with engaging in antisocial gameplay patterns, such as challenging or harassing other players (Bowman et al., 2012).

Conversely, players adopting a more social orientation are likely to empathise with avatars subjected to violence, potentially intervening on their behalf. Moreover, they might critically assess avatars perpetrating violence, taking actions to prevent such behaviour (Bowman and Banks, 2021). While different video game genres might be expected to influence the formation of player-avatar relationships, research by Bowman et al. (2016) found no evidence that these relationships significantly varied based on game type.

Yet, many aspects of player-avatar relationships remain unresolved within the burgeoning field of research. Questions persist about the player-side and game-side variables influencing the formation of these relationships. Additionally, the potential evolution of player-avatar relationships over time and the impact of developmental stages on the nature and consequences of these relationships beyond gameplay require further investigation. Banks (2015) discovered that individuals dealing with trauma tended to engage their avatars symbiotically, using the virtual realm for coping mechanisms or self-expression, indicating a potential therapeutic role for player-avatar relationships in dealing with real-world issues.

Storyline

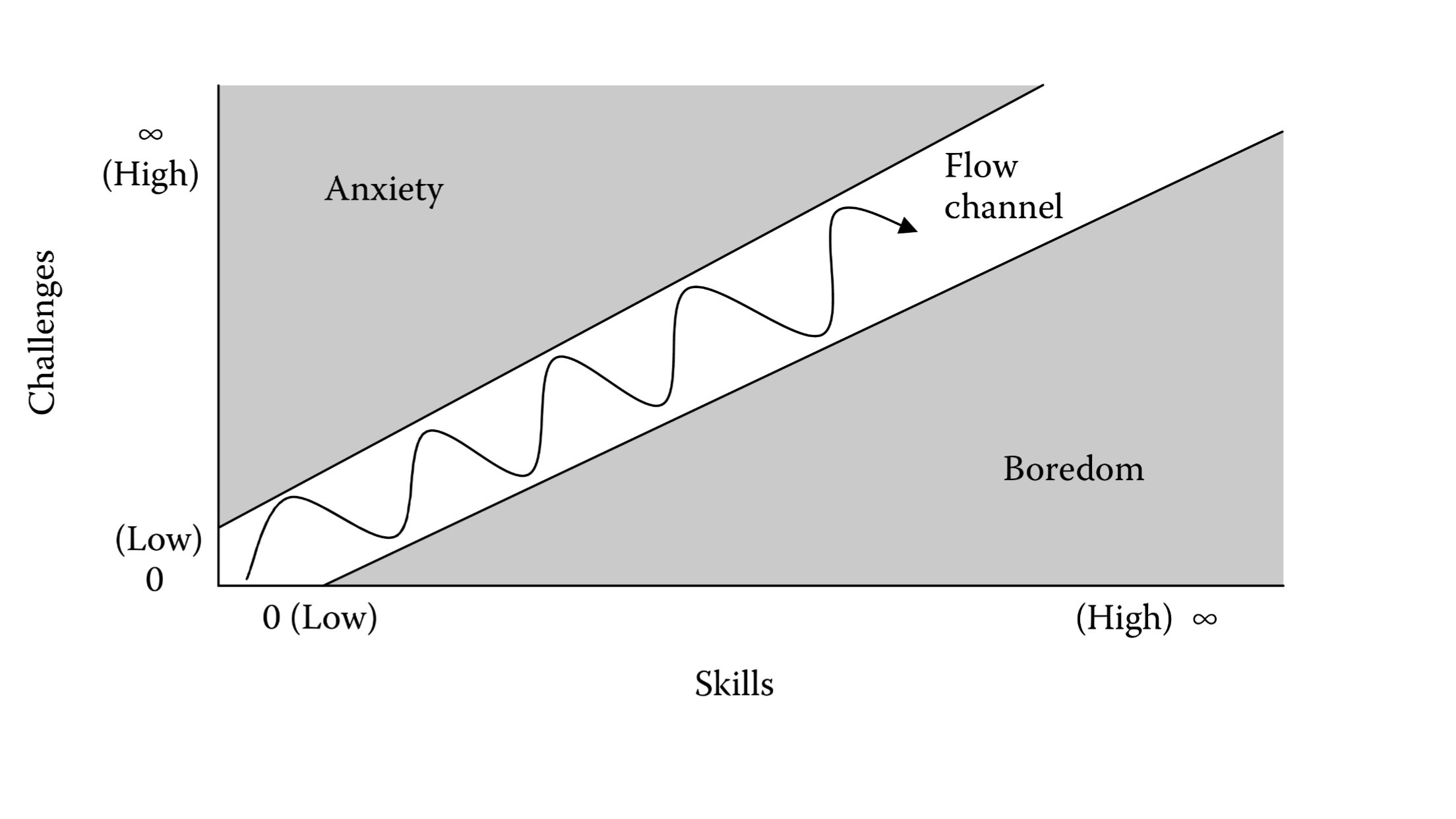

Fig1. Flow Channel theory from Jesse Schell

Last, but definitely not least, the storyline. Most popular games follow a narrative line, where the character, environment, or both, are undertaking a progressive development, based on the tasks & quests required to overcome the stages or levels of the game. A adequate, but also smooth transition, are usually success indicators of a storyteller or designer’s ability to empathise and engage accordingly, taking into account the player’s locus of control as well as the context in which it can develop. This is called a zone of proximal development, which can be seen as a goldilocks zone for where players are willing to put themselves through temporary hardships in order to grow and evolve. The locus of control is a psychological construct introduced by developer Julian B. Rotter in 1954, and it reflects an individual’s perspective on life and their tendency to attribute successes and failures to personal strengths and perseverance or external factors like fate. An individual’s locus of control is considered internal (described as “strong”) when they take responsibility for their life, believing they drive events and outcomes. On the contrary, an external locus of control (described as “low”) is characterised by the belief that life decisions are dictated by uncontrollable environmental factors, leaving everything to chance or luck, or under the influence of external authorities (Rotter, 1954, 1966).

In essence, here we face yet another universe that we’re just beginning to see unfolding. The intricate dynamics between players, avatars, NPCs and the environment in video games must be considered as a multifaceted exploration campaign, where the whole (experience) is greater than the sum of the parts. Understanding the nuanced nature of these relationships sheds light not only on how players respond to violent content but also on the potential psychological and therapeutic dimensions these virtual connections may carry over outside, in the physical environment.

As the gaming landscape evolves, further research is essential to unravel the complexities of player-avatar relationships and their broader implications for individuals navigating the immersive realms of interactive media.

Far-sighted implications

Studies have demonstrated that these embodied experiences lead to feelings of urgency and immediacy among users (Ahn, 2015; Ahn et al., 2016) and an increased sense of connection between the present and future selves (Hershfield et al., 2011).

How did violent games make their way into casual gaming?

Such a history reflects the dynamic interplay between gaming technology and cultural discourse. Exploring this narrative provides valuable insights into the evolving relationship between video games, technology, and societal perspectives.

While the impact of such games on real-world behaviour remains a topic of ongoing investigation, it is crucial to approach the subject with a balanced perspective. This section aims to explore the nuances of violent video games, acknowledging their cultural significance, psychological aspects, and the ongoing dialogue surrounding their potential effects on individuals and society.

Mortal Kombat

Warning: contains depictions of violence

One of the most violent, and popular, games from the 90’s whose franchise survives until today is Mortal Kombat.

By introducing violence as a goal in the very simple rules of survivor tournament landscape, the hand-to-hand combat and the opportunity for victorious players to perform graphic “fatalities,” including actions like ripping out an opponent’s still-beating heart, led to significant repercussions in the media. The game became a focal point for controversy, prompting multiple US Congressional hearings and ultimately contributing to the establishment of the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) system, designed to rate the content of video games (Andrews, 1993).

Hitman: Codename 47

Warning: contains depictions of violence

In 2000, Hitman: Codename 47 quickly becomes a big title in what can be perceived as “violent games”. Offering a range of options for eliminating targets, from classic approaches like stealthy poisonings and silent strangulations to more unconventional and elaborate methods such as disguising kills as accidents or utilising diverse weaponry. The game encourages strategic thinking and meticulous planning, providing players with the freedom to decide how they wish to accomplish their missions. This emphasis on diverse and inventive methods of assassination has contributed to Hitman’s reputation as a murder simulator, showcasing the game’s commitment to offering players a multitude of choices in how they approach their objectives.

Grand Theft Auto

Warning: contains depictions of violence

On a completely different scale, this time in an open world, where players can choose to engage with NPCs (and later on other players), the Grand Theft Auto (GTA) series underwent significant scrutiny due to its portrayal and, arguably, endorsement of physical, weapon-based, and vehicular violence, interwoven with themes that were criticised for their misogyny, racism, and other socially detrimental elements (Bowman, 2014a, b).

One distinguishing feature of the Grand Theft Auto series is its open-world design, providing players with a remarkable degree of agency within the game environment. Unlike more linear gaming experiences, GTA games offer expansive virtual landscapes where players can freely navigate, make choices, and influence the narrative. This open-world structure allows for diverse interactions with the game environment, including the perpetration of violent acts. The player’s agency extends beyond the main storyline, enabling them to engage in various side activities, explore the virtual world, and interact with non-playable characters (NPCs). This freedom of choice and extensive player agency contributes to the complex discussion surrounding the impact of violent content in video games, as players can actively shape their experience within the game world.

Because of this, the games within the Grand Theft Auto series often encountered sales restrictions, typically receiving a mature audience rating (M). However, despite these controversies, the latest installment in the series, Grand Theft Auto V, achieved remarkable success by selling a record-breaking 110 million copies as of May 2019 (Kain, 2019).

Spec Ops: The Line

Warning: includes scenes of graphic violence and gore

In the last decade, we see more morally complex themes introduced in games. Walt Williams, the lead writer of Spec Ops: The Line, elucidated the underlying philosophy behind his creation. While the game adheres to the military-themed genre, characterised by intense warfare and weapon-centric combat typical in many third- and first-person shooter games, what sets Spec Ops: The Line apart is its unique approach to contextualising on-screen violence. Through the many challenges in the game, the players are exposed to themes of rationalising and character development in the vast moral landscape of a choice. A pivotal moment unfolds when the protagonist, Walker, faced with intense enemy fire, chooses to deploy a white phosphorus canister (a chemical weapon) against opposing forces, despite the objections of fellow soldiers. Navigating the aftermath of this decision, players are confronted with the harrowing consequences of chemical warfare. Notably, the closing scene, depicting the tragic aftermath— a mother cradling her daughter amid severe burns—drew criticism from gaming journalists for its graphic portrayal and the game’s inclusion of what some deemed as player-enforced war crimes (Roberts, 2014).

In response to these critiques, Williams (2013) clarified that the game’s intent was to contextualise, rather than glorify, the realities of war. The unfolding narrative following this scene traces Walker’s gradual descent into mental turmoil as he grapples with a series of morally challenging situations involving gruesome acts of war. This deliberate design choice aimed to engage players in a reflective examination of the psychological toll of war, steering away from the conventional glorification often associated with violence in video games.

Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2

Warning: includes scenes of severe body injuries

In *Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2*, players confront a controversial scenario where they are immersed in a terrorist cell targeting civilians in an airport. Faced with the disturbing choice of either shooting innocent civilians or witnessing the terrorists’ brutality, the level design sparked criticism for its gratuitous and superfluous nature. The game’s writers defended their intent, expressing a desire to elicit any emotional response from players (Totilo, 2012). The execution of this scenario faced backlash during play-testing, with objections to its content, and some players refusing to participate (Evans-Thirlwell, 2016).

I could have taken it to a much darker place, but that would have been just for shock value.

— Mohammad Alavi, video game developer who formerly worked at Respawn Entertainment

Whereas in contrast, Spec Ops: The Line mentioned above earned widespread acclaim for its nuanced incorporation of moral conflict, positioning it among the top-tier video games in the history of the medium, primarily attributed to its morally intricate storytelling. Notably, the comparison between the two games underscores the critical reception of *Spec Ops: The Line* as opposed to the contentious nature of *Call of Duty*’s scenario. This dichotomy highlights the potential evolution in narrative design within video games, with suggestions that the medium’s portrayal of violence may transcend controversy to be recognised as a form of art (Wells, 2016).

Violence and Interactive Media

Violence can be defined as the deliberate application of physical force or power, whether in the form of a threat or actual action, directed towards oneself, another individual, or a collective entity. Its consequences encompass injury, death, psychological distress, impaired development, or deprivation, as outlined by Krug et al. (2002).

One of the foundational theories for aggression in psychology was pioneered by Bandura (1986), teaches us that that children, and subsequently young adults, exposed to adults aggression will tend to display verbal and/or physical aggressive behaviours. This effect formed the basis of his social learning theory, where he contends that the aptitude for constructing cognitive models through symbolisation and abstraction enables individuals to comprehend and assimilate information from both direct and indirect, vicarious experiences.

Media effects lack a universal definition, but research typically concentrates on how various forms of mediated communication, including printed books, television shows, video games, and VR, influence the thoughts, emotions, and behaviours of the end user. Rutledge (2013) similarly defines media psychology as the study of the intricate relationship between humans and the evolving technological environment.

The interactive aspect mentioned involves the user’s capability to modify the form or content of the mediated experience (Steuer, 1992), especially pertinent to violent content. Rather than passively observing on-screen violence, interactive media engages the user directly in the perpetration of such acts.

Over decades, research on mass media has consistently shown that consuming mass media messages influences real-world outcomes, spanning changes in health behaviour (Wakefield et al., 2010), shifts in attitudes toward social issues (McLeod and Detenber, 1999), and learning (Papa et al., 2000).

Virtual Reality

Warning: includes scenes of graphic violence

Newer technologies like VR, which has large applications in the interactive media industries, has almost bridged the two worlds, adding another layer of complexity to the user-media relationship, and increasing in-game agency, shifting user perception from observer to protagonist. With new barriers removed, they are now in full control over their field of view, corresponding locomotion in time and scale, object manipulation and interaction. Compared to traditional media, this is offering an immersive, almost first-hand, experience (Blascovich and Bailenson, 2011).

Stober (2004) and Bowman (2019) propose that the progression of video games toward more serious, contemplative content aligns with a historical trend observed in evolving media entertainment. This shift, driven by advancements in communication technologies, mirrors a pattern where content evolves from basic technological showcases to innovative and unique storytelling approaches.

Examining specific games, developers strategically incorporate elements from established media forms to elicit diverse reactions from players. For instance, war films, known for employing realistic and graphic violence for somber anti-war messages (Gates, 2005), influence the design of video games. Oliver and Raney’s (2011) dual process model, distinguishing between hedonic enjoyment and eudaemonic appreciation, and the subsequent development of the concept of self-transcendence by Oliver et al. (2018), offer frameworks to understand audience reactions beyond mere enjoyment. Applied to video games, known for their emotional depth, these models suggest players undergo a spectrum of emotions in response to in-game actions, reflecting on their consequences both within the game and in the real world (Hemenover and Bowman, 2018).

Because of the greater weight placed on direct, rather than indirect, experiences tend to have stronger and longer lasting impact on attitude changes than indirect experiences (Fazio and Zanna, 1981), newfound moral & ethical dilemmas — not just for gamers, but also the game writers, character creators, level designers and all the way to company culture — must be tackled proportionally.

Gamer rage

Warning: contains violent behaviour (comical)

Gamer rage and its various manifestations:

- Verbal expressions: Many children expressed their rage by crying, yelling, and cursing. The intensity of verbal expressions varied, with some being louder when playing with friends and in group chats.

- Physical expressions: Rage sometimes escalated to physical actions, such as throwing phones, game controllers, and other items, kicking and beating game consoles and computers, and even slamming tables. This physical rage could result in material damage, leading to broken gaming equipment and the need for replacements.

- Quitting: In response to their anger, some children chose to quit gaming either spontaneously or thoughtfully. This quitting was often done to prevent overreactions, avoid saying regrettable things, or breaking gaming equipment. It was also seen as a way to improve their performance in the game. Some children quit gaming temporarily, opting for outdoor activities or switching to less frustrating games, while others made more permanent decisions to uninstall or quit playing certain games altogether.

FIG 1. Infographic on the reasons and manifestations of children’s gamer rage.

Always good to keep in mind that this short-term increase in aggression does not necessarily translate into long-term, real-world violent behaviour. Research has failed to establish a direct, causal link between violent video game exposure and criminal violence (Ferguson, 2015). A comprehensive analysis by the American Psychological Association (APA) found insufficient evidence to support the assertion that violent video games directly lead to criminal violence (APA, 2017). It is crucial to differentiate between short-term increases in aggression and long-term, real-world violent actions.

Stay informed

It is essential for parents and guardians to stay well-informed about the developmental stages of their children, as this knowledge can help guide their responsible and strategic use of technology. As with many complex problems in life, a balanced approach is needed.

It is important to well-informed about the developmental stages and continue on your quest to find ways of promoting healthy technology use for children, and ensure that technology plays a positive and supportive role in your child’s development.

Digital guidelines: Promoting healthy technology use for children

Pointers for parents to keep in mind when establishing guidelines for children’s technology use, in a world where many children have a tablet or smartphone

Further research is crucial to comprehensively grasp the ramifications of interactive media violence across various layers of the social ecology. Such insights hold the potential to create a more robust understanding of digital violence and how it translates to media & and cyberpsychology to enhance the efficacy of public health strategies aimed at violence prevention.

Additionally, the age at which children and adolescents are exposed to violent video games matters. Various researchers argue that older adolescents may be less susceptible to the potentially harmful effects of violent video games than younger children (Ferguson, 2015). As adolescents’ cognitive and emotional development progresses, their ability to distinguish between fantasy and reality and to critically evaluate media content also improves. This developmental stage may contribute to a reduced likelihood of violent video games having a significant influence on behaviour (Calvert et al., 2017; Gentile et al., 2004).

We hope you have enjoyed our quick introduction and make sure to check the resources available

For final thought it’s good to remember that while there is evidence supporting a link between violent video games and short-term increases in aggression, there is no clear, direct connection between video game exposure and long-term, real-world violent behaviour. It is essential to consider the developmental stage and cognitive abilities of the individual. Video games should be assessed within the broader context of a child’s environment, including family dynamics, peer influences, and mental health, as these factors also play a significant role in shaping behaviour. Therefore, the debate should continue to be grounded in empirical research and a holistic understanding of the complex factors contributing to violent behaviour.

Resources

Addiction Risk Assessment Quiz

Assessment Quiz by Clinical Psychologist Dr. Brent Conrad (this is not a substitute for a medical diagnosis).

Ahn, S. J., Fox, J., Dale, K. R., and Avant, J. A. (2015). Framing virtual experiences: effects on environmental efficacy and behavior over time. Communication Research 42(6), 839–863. doi: 10.1177/0093650214534973

Andrews, E. L. (1993). Industry set to issue video game ratings as complaints rise. The New York Times.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Banks, J. (2015). Object, Me, Symbiote, Other: A social typology of player-avatar relationships. First Monday. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v20i2.5433.

Blascovich, J., and Bailenson, J. (2011). Infinite reality: avatars, eternal life, new worlds, and the dawn of the virtual revolution. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Bowman, N. D. (2014a). “Grand Theft Auto,”. In M. Eastin, Encyclopedia of Media Violence, pp 189–191. Thousand Oaks, California.

Bowman, N. D. (2014a). “Grand Theft Auto,”. In M. Eastin, Encyclopedia of Media Violence, pp 189–191. Thousand Oaks, California.

Bowman, N. D. (2019). Editorial: Video games as demanding technologies. Media and Communication, 7(4), 144–148. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v7i4.2684.

Bowman, N. D., Ahn, S. J., & Kollar, L. M. M. (2020b). The paradox of interactive media: the potential for video games and virtual reality as tools for violence prevention. Frontiers in Communication, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.580965.

Bowman, N. D., Ahn, S. J., & Kollar, L. M. M. (2020b). The paradox of interactive media: the potential for video games and virtual reality as tools for violence prevention. Frontiers in Communication, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.580965.

Bowman, N. D., Banks, J., and Downs, E. P. (2016). The duo is in the details: game genre differences in player-avatar relationships. Select. Papers Internet Research 6. Accessed November 4, 2023 https://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/spir/article/viewFile/9032/7127.

Bowman, N. D., Schultheiß, D., & Schümann, C. (2012). “I’m attached, and I’m a good Guy/Gal!”: How character attachment influences pro- and Anti-Social motivations to play massively multiplayer online Role-Playing Games. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(3), 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0311.

Bowman, N. D., Ahn, S. J., & Kollar, L. M. M. (2020b). The paradox of interactive media: the potential for video games and virtual reality as tools for violence prevention. Frontiers in Communication, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.580965.

Calvert, S. L., Appelbaum, M. I., Dodge, K. A., Graham, S., Hall, G. C. N., Hamby, S., Fasig-Caldwell, L. G., Citkowicz, M., Galloway, D. P., & Hedges, L. V. (2017). The American Psychological Association Task Force assessment of violent video games: Science in the service of public interest. American Psychologist, 72(2), 126–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040413.

De Borst, A. W., Sanchez-Vives, M. V., Slater, M., & De Gelder, B. (2020). First-Person Virtual Embodiment Modulates the Cortical Network that Encodes the Bodily Self and Its Surrounding Space during the Experience of Domestic Violence. ENeuro, 7(3), ENEURO.0263-19.2019. https://doi.org/10.1523/eneuro.0263-19.2019.

Evans-Thirlwell, E. (2016). Ghillied Up to No Russian, the making of Call of Duty’s most famous level. PCGamer. Accessed November 4, 2023. https://www.pcgamer.com/from-all-ghillied-up-to-no-russian-the-making-of-call-of-dutys-most-famous-levels/2/.

Fázio, R. H., & Zanna, M. P. (1981). On the predictive validity of attitudes: The roles of direct experience and confidence1. Journal of Personality, 46(2), 228–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1978.tb00177.x.

Ferguson, C. J. (2015). Do angry birds make for angry children? A Meta-Analysis of video game influences on children’s and adolescents’ aggression, mental health, prosocial behavior, and academic performance. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(5), 646–666. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615592234.

Gentile, D. A., Lynch, P., Linder, J. R., & Walsh, D. (2004). The effects of violent video game habits on adolescent hostility, aggressive behaviors, and school performance. Journal of Adolescence, 27(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.10.002.

Hemenover, S. H., & Bowman, N. D. (2018). Video games, emotion, and emotion regulation: expanding the scope. Annals of the International Communication Association, 42(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2018.1442239.

Hershfield, H. E., Goldstein, D. G., Sharpe, W. F., Fox, J., Yeykelis, L., Carstensen, L. L., & Bailenson, J. N. (2011). Increasing saving behavior through Age-Progressed renderings of the future self. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(SPL), S23–S37. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.48.spl.s23.

Kain, E. (2019). Putting Grand Theft Auto V’s 110 million copies sold into context. Forbes.

Krug, E. G., Dalhberg, L. L., Mercy, J. A., Zwi, A. B., and Lozano, R. (2002). World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

McLeod, D. M., & Detenber, B. H. (1999). Framing effects of television news coverage of social protest. Journal of Communication, 49(3), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1999.tb02802.x.

Oliver, M. B., and Sanders, M. (2004). “The appeal of horror and suspense,” in The Horror Film, ed S. Prince (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press), 242–260.

Oliver, M. B., & Raney, A. A. (2011). Entertainment as pleasurable and Meaningful: Identifying hedonic and eudaimonic motivations for entertainment consumption. Journal of Communication, 61(5), 984–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01585.x.

Oliver, M. B., Raney, A. A., Slater, M. D., Appel, M., Hartmann, T., Bartsch, A., Schneider, F. M., Janicke‐Bowles, S. H., Krämer, N. C., Mares, M. L., Vorderer, P., Rieger, D., Dale, K. R., & Das, E. (2018). Self-transcendent media experiences: taking meaningful media to a higher level. Journal of Communication, 68(2), 380–389. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqx020.

Papa, M. J., Singhal, A., Law, S., Pant, S., Sood, S., Rogers, E. M., & Shefner‐Rogers, C. L. (2000). Entertainment-Education and Social Change: An analysis of parasocial interaction, social learning, collective efficacy, and Paradoxical communication. Journal of Communication, 50(4), 31–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02862.x.

Roberts, S. (2014). Now playing: Spec Ops’ most troubling scene. PC Gamer. Accessed November 6, 2023 https://www.pcgamer.com/now-playing-spec-ops-most-troubling-scene/.

Rotter, J. B. (1954). Social Learning and Clinical Psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. The Psychological Monographs, 80(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976.

Rovira, A., Swapp, D., Spanlang, B., and Slater, M. (2009). The use of virtual reality in the study of people’s responses to violent incidents. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.059.2009.

Rutledge, P. (2013). Arguing for media psychology as a distinct field. In Oxford University Press eBooks (pp. 43–61). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195398809.013.0003.

Seinfeld, S., Arroyo-Palacios, J., Iruretagoyena, G., Hortensius, R., Zapata, L. E., Borland, D., De Gelder, B., Slater, M., & Sanchez-Vives, M. V. (2018). Offenders become the victim in virtual reality: impact of changing perspective in domestic violence. Scientific Reports, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19987-7.

Silverman, B. (2007,). Controversial games. Yahoo! Games. Accessed November 6, 2023 https://web.archive.org/web/20070922155732/http://videogames.yahoo.com/feature/controversial-games/530593.

Stöber, R. (2004). What media evolution is: a theoretical approach to the history of new media. European Journal of Communication, 19(4), 483–505. doi: 10.1177/0267323104049461.

Totilo, S. (2012). The designer of Call of Duty’s ‘No Russian’ massacre wanted you to feel something. Kotaku. Accessed November 6, 2023 https://kotaku.com/the-designer-of-call-of-dutys-no-russian-massacre-wante-30777344.

Wells, G. (2016). Shakespeare’s influence on video game violence: death and gore in Titus Andronicus. Gamasutra. Accessed November 7, 2023 https://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/GregoryWells/20160209/265404/Shakespeares_Influence_on_Video_Game_Violence_Death_and_Gore_in_Titus_Andronicus.php.

Wakefield, M., Loken, B., & Hornik, R. (2010). Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. The Lancet, 376(9748), 1261–1271. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60809-4.

Williams, W. (2013). We are Not Heroes: Contextualizing Violence Through Narrative. San Francisco, CA: Game Developers Conference Vault.